The daylight sacrifice in the folk horror classic The Wicker Man is deeply horrifying. The people of the fictional Summerisle are acting based on a belief system that is, to them, perfectly logical. The act has the appearance of being of some ancient faith, however, it becomes clear it’s been recently invented. It is disconcerting that such archaic-seeming belief systems exist in the modern world and it becomes terrifying that otherwise enlightened people are willing to commit human sacrifice based on it.

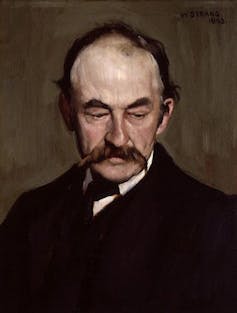

In my forthcoming book, Thomas Hardy and the Folk Horror Tradition, colleagues and I suggest that this strand of folk horror is far more terrifying than anything supernatural, precisely because of how ordinary it is.

The terror of folk horror is evoked by something much darker than the simple presence of ghosts or ghouls. While the genre is difficult to define, the four key elements identified by writer Adam Scovell are landscape, isolation, a skewed belief system and happening/summoning.

Mining the past

Probably the story of Hardy’s that most exemplifies the folk horror tradition is The Withered Arm published in The Wessex Tales (1888). In the story a moral transgression and jealousy manifest themselves as a physical ailment, which can only be “cured” by placing the limb on the neck of a hanged man.

The origins of this “cure” are unclear, is it Hardy’s invention or is it from folklore? We know that Hardy did witness executions in 1860 and, in the moment of reading, it has the appearance of reality. The reader is drawn into a world of archaic superstition, which challenges how “enlightened” we are.

Hardy embraced the tradition of his rural Dorset childhood, which was infused with folk tales and superstition, and this sat uneasily alongside his place in the modern world. He was, as described by Claire Tomlin in her expansive biography, a “time-torn man”.

Hardy was writing in a period of significant social change. Industrialisation and urbanisation were well underway and much of his writing is set in a fictional place called Wessex that stands aside from the modern world, trapped in memory. Hardy looked to his childhood for inspiration and was, perhaps like all of us, most susceptible to suggestion as as child. Folk horror stories can take us back to that time in our lives.

Cultural hauntings

This “looking back” in Hardy’s stories can be defined as “hauntological”, something which infuses a lot of contemporary folk horror. Coined by the French post-structuralist critic Jaques Derrida in 1993 and perhaps most notably developed by the cultural critic Mark Fisher, “hauntology” describes the process of time folding back on itself. It is that which is infused with our cultural past.

We can see this now with the prevalence of contemporary writers looking back to their childhoods in the 1970s and 1980s. In Britain, this period has taken a very dark turn in recent years with revelations about popular cultural figures (many childhood TV stars like Jimmy Saville), who now haunt the collective cultural psyche.

As the media academic Diane A. Rodgers argues, “hauntology” is a term that regularly appears alongside folk horror to describe TV, films, novels and music that evoke a sense of troubled nostalgic reverberation.

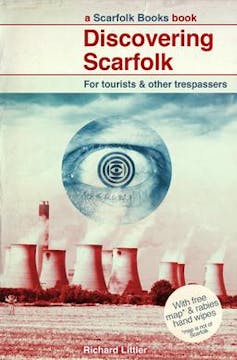

A good example of this is Scarfolk Council, which was created by graphic designer Richard Littler. The project began as a blog made up of fake historical documents parodying 1970s British public information posters. They told of a town in northwest England that did not progress beyond 1979. Instead, as the blog describes, “the entire decade of the 1970s loops ad infinitum. Pagan rituals blend seamlessly with science. Hauntology is a compulsory subject at school, and everyone must be in bed by 8pm because they are perpetually running a slight fever.”

The blog is a satirical look at the 1970s but also uses the past to comment on the present. Themes of suburban life in fading northern towns, religion, racism, sexism as well as occultism and religion are touched upon.

Education is also a common theme. Take, for instance, a post about a school textbook that was full of erroneous and harmful information.

The Let’s Think About… booklet was published by Scarfolk Council Schools & Child Welfare Services department in 1971. It was designed for use in the classroom and encouraged children between the ages of five and nine to focus on a series of highly traumatic images and events.

Despite the book being based on no research and written by a murderous local dinner lady, it remained on the school curriculum for many years, notes the post. A commentary, perhaps, on memories of cold 1970s classrooms and lukewarm bottles of milk. Scarfolk is so effective and unsettling as these memories still haunt many of us as adults.

This satirical drawing of the past into the present echoes Hardy’s Wessex, which was so clearly and directly based on Dorset. There is a sense of horror created by Wessex and Scarfolk being worryingly close to the real world.

As with Hardy, contemporary writers of hauntology are looking back to their childhood as the source of our contemporary fears. What is different for these artists is that this is a past many of us share – an era of three TV channels where we all watched the same shows. This retreat into the recent past is the foundation of contemporary folklore, but instead of a forgotten secluded rural community, these are representations of isolated (often northern) towns which feel forgotten – lost in time. This looking backward is more than mere nostalgia. We (like Hardy) are haunted by our cultural past.

This Halloween you could pop down to a supermarket to buy a Frankenstein mask for a jolly celebration, or you could terrify the locals by dressing in a Velour tracksuit. The real fear of folk horror is that it reveals that the monster is within and perpetually present.