Nigeria is experiencing a major conflict between nomadic herdsmen and indigenous farmers. In 2016, the conflict led to the death of 2,500 people, displaced 62,000 others and led to loss of US$13.7 billion in revenue. In January 2018 alone, the conflict claimed the lives of 168 people.

The herdsmen are predominantly Fulanis, a primarily Muslim people scattered throughout many parts of West Africa. The farmers, meanwhile, are mostly Christian. Therefore, when violence erupts between the two groups, with symbolic results like churches being burnt down, it is unsurprising that the dominant narrative in Nigeria and abroad is that this is a conflict motivated by religion and ethnicity.

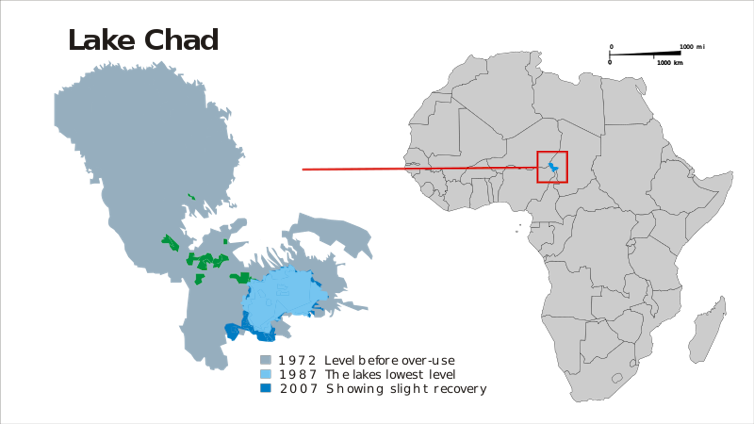

What’s missing is the environmental perspective. Nigeria spans more than 1,000km from a lush and tropical south to the fringes of the Sahara Desert in the north. And, in Nigeria, the Sahara is moving southward at a rate of 600 metres a year. At the same time, Lake Chad in the country’s far north-east has largely dried up. Fulani herdsmen who once relied on the lake have thus moved further south in search of pasture and water for their livestock. The further south you move, the more the population becomes Christian, hence when resource conflicts emerge they appear religious.

Such conflicts between herdsmen and farmers aren’t entirely new. A drought in the late 60s, for instance, kicked off struggles over land use across the Sahel, and the Fulanis do have a history of strategic annexation of territories. What’s new this time round is that the conflict has taken on an entirely different scale, as a problem once restricted to the north of Nigeria has become a major issue in the country’s south.

This is because environmental devastation has necessitated widespread migration of Fulanis from all over West Africa to the south of Nigeria, which has been unable to prevent nomads from other countries from coming in along its long borders. The influx of new people has disrupted the existing dynamics and relationship between predominantly farming local communities and nomadic herdsmen.

But environmental explanations are largely ignored in favour of talk of ethnic or religious conflict. Such talk quickly becomes highly emotive, preventing a full analysis of all the driving forces behind the conflict. The dominance of the “ethnic war” narrative therefore makes it harder to develop holistic and sustainable solutions and, in a country that is a mix of cultures and religions, puts national unity and peace-building at risk.

Silence from the authorities

The government’s response to all this has been near silence. In the vacuum, political explanations have emerged, often from people with a vested interest. For instance, elites and political leaders from affected regions suspect the president, Muhammadu Buhari, who himself is Fulani, of being complicit in the attacks (though they have stopped short of directly accusing him). There’s no evidence the president has anything to do with the conflict but, in a hierarchical society like Nigeria, the word of elites can be taken as gospel.

The central government has proffered solutions such as cattle “colonies”, which take lands from indigenous farmers and give it to the Fulanis to graze. But among the farmers this only reinforces worries of an ethnic land grab.

The president has often spoken of “recharging” Lake Chad to its former size, perhaps using water diverted from the Ubangi River in the Congo basin, and he recently spoke on the subject at an African Union conference. Yet the lake still is not really built into the government’s strategy for the farmer-herder conflict.

Healthy lake, peaceful people

So what would a sustainable and just solution to the conflict actually involve? Lake Chad certainly will need to be “recharged”, along with a massive programme of tree growing and sustainable water management. This will require the engagement of neighbouring countries – who have serious environmental problems of their own – and the support of international donor agencies, but it would go a long way towards stemming the migration southward and should reduce incidences of conflict.

The government must also recognise, publicly, that this is at root a conflict over resources exacerbated by environmental problems. It must point this out when the need arises, rather than waiting until half-truths dominate public discourse.

The Nigerian media, for its part, often thrives on emotive narratives. But this story of conflict between herders and farmers calls for less sensationalism and more investigative journalism that helps reveal further nuances to the complex issue. This isn’t a simple tale of ethnic conflict – the environment cannot be ignored.