Depending on who you are, Titania McGrath’s tweets offend, baffle or inspire you – or you just might find them hilarious. Since April 2018, McGrath – who describes herself on her Twitter page as: “Activist. Healer. Radical intersectionalist poet. Selfless and brave” has been, tweeting several times a day from the perspective of a young and “woke” left-wing, woman. At the most recent count she has 242,000 followers.

But she isn’t real. McGrath is, in fact, the invention of comedian Andrew Doyle, a columnist for Spiked magazine and co-writer of the scripts delivered by the equally fictitious news reporter, Jonathan Pie.

It might seem that the Titania McGrath phenomenon could only happen in the social-media obsessed world of 2019, but this kind of satirical hoax has been happening since the 18th century.

The McGrath story recalls that of 18th-century astrologer Isaac Bickerstaff. In February 1708, Bickerstaff published an almanac in which he foretold the death of John Partridge, a controversial social commentator who had recently offended many with his criticism of the Anglican Church. This was followed on March 31 by a pamphlet confirming that Partridge had indeed now died.

But Partridge wasn’t dead. When he awoke on April 1 he was met with questions about his own funeral. He quickly published a pamphlet asserting that he was alive, but Bickerstaff coolly rejected it as a ghoulish hoax. He claimed that anyone who spoke to Partridge’s wife would hear that he had neither “life nor soul”. Unfortunately for Partridge, the public believed Bickerstaff.

Bickerstaff was later revealed to be a fictional persona created by the celebrated satirist Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels. Swift, concerned by what he considered to be Partridge’s dangerous views on the church, had decided to take him down a notch or two. As April’s Fool jokes go, Swift’s perhaps went too far.

Read more: Eight surprising things it's time you knew about Gulliver’s Travels

Unspeakable thoughts

Bickerstaff and McGrath were both created to critique views that their creators objected to. Doyle has said that McGrath was designed to satirise a perceived obsession with identity politics and social justice.

The name Titania is a conscious reference to Shakespeare’s Queen of the Fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, said Doyle. She – or people like her – live in a fantasy world that is so powerful in its policing of language and thought that many things have become unsayable.

Wherever our sympathies might lie in response to such claims, the McGrath account and the responses to it have much to tell us about the current climate for satire and about satire’s history.

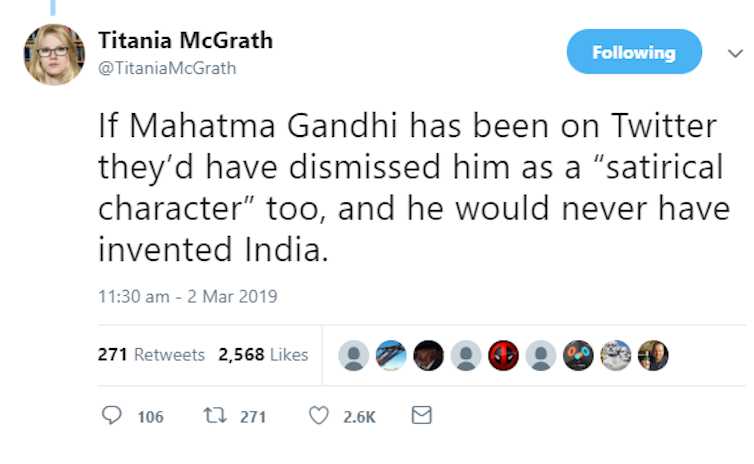

The Titania McGrath project was helped by the speed with which Twitter allows its users to post and retweet. One of the account’s most “liked” tweets amassed more than 20,000 likes in 11 days, not to mention nearly 2,000 comments.

It’s easy to assume that this could only happen in the age of the internet – but Swift’s readers were in a very similar situation. Along with lapses in licensing rules, cheap print – much like social media – meant that suddenly more and more people could publish material. This explosion of print was directly responsible for a literary period often heralded as the great age of British satire. For Swift, Alexander Pope, Lady Mary Montagu and many other satirists, print provided their targets, their platform and their audience.

Reading 21st-century social media, like reading 18th-century print, sometimes means not knowing whether you are reading fact or fiction – or indeed whether the person who wrote what you are reading is really who they say they are. Under these conditions, a Bickerstaff or a McGrath can emerge all too easily.

You can fool some people …

Many Twitter users realised quickly that McGrath was intended as satire, and indeed sought to join in with the joke. Others took the picture of a young woman as a representation of reality and sought to correct and edify her. Others still frequently ask: “Is this satire?” – a response which can indicate genuine confusion, but which is also itself a rhetorical move (“this is so stupid it must be satire!”)

All three of these categories of response enabled the McGrath account at least partly to fulfil its mission: to shine a light on – and invite ridicule of – the folly Doyle perceives in society. Similarly, Swift used Bickerstaff to articulate his concerns with Partridge’s rhetoric in a way he never could as himself.

It sometimes seems like our world is more complicated than ever, but it’s useful to remember that so much of this has happened before. Doyle and Swift each created personas, exploiting a media climate where truth is hard to verify. At the same time, though, they used these fictional personas to speak a truth they felt they couldn’t convey otherwise. Perhaps the most crucial element in the success or failure of personas like these is how receptive the audience is to the message that the would-be satirist wishes to convey.