Brexit inevitably means Britain will have to make some difficult foreign policy choices. The UK prime minister, Boris Johnson, will certainly prioritise strengthening the so-called “special relationship” with the US. But efforts will also likely be made to rekindle historic ties to Britain’s former colonies in the Commonwealth.

Some members of government still seem to hold nostalgic aspirations to establish what Whitehall officials reportedly once termed “Empire 2.0” in March 2017.

Such thinking is based on a potent image of a Commonwealth “golden age” in the years between the second world war and Britain’s first application to join the European Economic Community (EEC). Yet the political, strategic and economic relationships within the Commonwealth between 1945 and 1961 were far from harmonious. The former colonies pursued their own national interests and were no longer willing to follow Britain’s lead.

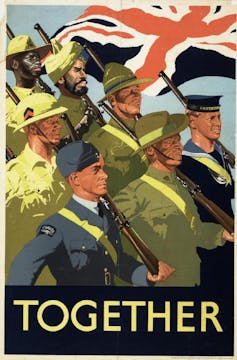

Undoubtedly, the unity of the “old” Commonwealth members – Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa – against the axis powers in the second world war did represent the pinnacle of Commonwealth cooperation.

The post-war Labour government at the time hoped to use Commonwealth leadership to retain Britain’s great power status. The other Commonwealth governments, however, had become frustrated by Britain’s superior attitude during the war and wanted to demonstrate their sovereignty.

More significantly, to prevent India from leaving when it became a republic in 1949 – and to discourage other nations from wanting to leave too – common allegiance to the Crown was removed as the essential criteria for membership and the word “British” was dropped from the organisation’s title. These reforms crucially recast the Commonwealth as an organisation of equals. It was a partnership no longer based on imperial ties but on shared values and its multi-ethnic nature.

Old and new

Still, the Commonwealth soon became divided along its “old-new” racial axis. Most notably, the “new” members, initially India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka and later joined by Malaysia, Ghana and Nigeria, championed anti-colonialism, locked horns with South Africa over apartheid, and deeply criticised Britain’s military actions during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Moreover, by the early 1960s, after decolonisation, the organisation’s composition had tipped in favour of the “new” members. Britain had become the target of criticism over South Africa and Rhodesia.

In the cold war, Britain also hoped its Commonwealth partners would help defend the Empire. But the second world war had shown the other Commonwealth nations that Britain could no longer protect them. When the threat of conflict once again loomed, they only halfheartedly entered into strategic planning with London.

Instead, most Commonwealth members – including Britain itself – looked increasingly to Washington for their security. Canada already had its own security relationship with the United States while in 1951 the Australia, New Zealand and United States (ANZUS) Treaty was signed without Britain.

Many “new” members even pursued a policy of neutrality in the cold war, refusing to enter into military alliances with either Washington or Moscow.

Trade deals and loans

After the second world war, cash-strapped Britain put great stock in Commonwealth trade to help with economic recovery. But in 1945-6, the Labour government also sought a $3.75bn loan from the United States. Yet Washington made this loan conditional on the gradual erosion of the system of imperial preferences that protected trade between Britain and its Commonwealth partners from external competitors, including the United States. As a result, Commonwealth markets for British goods could no longer be guaranteed. Moreover, Canadian trade with Britain had already significantly declined since it had traded principally with its southern neighbour for decades.

In contrast, in 1945 Britain was easily Australia, New Zealand and South Africa’s largest market for their exports and the greatest supplier of their imports. These countries, though, soon developed regional trade links of their own, and ties with Britain steadily declined. Similarly, the “new” members gradually moved out of Britain’s imperial trading system as they sought greater autonomy. At the same time, Britain increasingly traded with Europe, prompting Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan’s application to join the EEC in 1961.

So what does the Commonwealth experience during the organisation’s so-called “golden age” suggest for Britain after Brexit?

Not even the most ardent advocate of “Empire 2.0” wants to turn the Commonwealth into a British-led military alliance. The United States will remain the UK’s key security partner. History also indicates that Britain will not be able to wield political leadership over the Commonwealth. Indeed, London has not done so since the second world war and any attempt now would likely lead to the organisation’s collapse.

Could “turbo-charging” Commonwealth trade – as the organisation’s secretary-general, Patricia Scotland, proposed in July 2016 – resolve possible economic difficulties after Brexit? Australia, New Zealand, India and some smaller Commonwealth members have indicated they want to increase trade with Britain. Yet these countries are more interested in selling goods to Britain rather than buying British goods. Furthermore, in 2018 just 8.1% of Britain’s exports went to distant Commonwealth countries compared to 45% to the neighbouring EU.

It will take considerable time and effort to alter this balance, especially since Commonwealth countries have long ago found alternative regional markets. Much will also depend on what kind of future trade deals Britain negotiates with both the EU and the United States.