The adult animated satire, The Prince, has sparked outrage for its portrayal of the British royal family as a mob of hyper-privileged halfwits, hopelessly out of touch with contemporary society. They are led by Queen Elizabeth II, imagined here as a bling-coated mafia boss.

The Telegraph described the show as “grossly offensive”. While The Washington Post reported that a torrent of complaints labelled it “wrong”, “disgusting” and guilty of fuelling “hatred toward Britain’s royals”.

But The Prince is far from the first instance of satire to poke fun at the royal family – nor is it the most biting in this 300-year-old tradition.

In many ways, royal figures are the perfect subjects for satire. Traditionally, the satirist seeks to reveal and skewer stupidity, ridiculousness and hypocrisy and, in most cases, speak truth to power. This process inevitably constitutes “punching up”. This means targeting those with more privilege and a higher status in society than the satirist.

However, in recent years the royals have been rebranded as vulnerable, despite their enormous privilege. This change might have significant consequences for the art of satire.

Punching up

The royal family’s position at the top of British society makes them an obvious satirical target. Perceptions of the royal family as antiquated and politically redundant, despite their immense fortune and revered status, are fertile material for satirists seeking to lampoon ridiculousness and hypocrisy.

For as long as the royals were seen as aloof, untroubled and of a different breed from the commoners over whom they ruled, satirists haven’t needed to concern themselves with questions about the harm such satire might do to the royal family as “real” people.

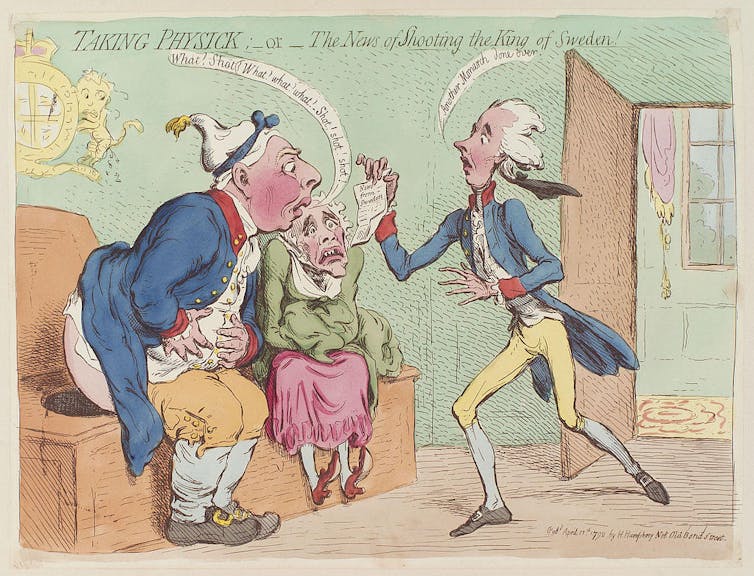

In fact in the 18th century, when satire of the royals was at its most scathing, scandalous and scatological (there was a lot of poo involved), it drew little attention from the monarchy.

During this period, caricaturist James Gillray would regularly produce images of George III and his wife defecating. He also drew Queen Charlotte haggard and naked, and their son George IV as a sexually ravenous libertine emerging from beneath a woman’s skirts. Nevertheless, James Gillray was still granted a government pension.

The monarchy’s tolerance of such satire spoke to their strength. They were so secure in their position of power that they were untroubled by cheap jokes and toilet humour. There are even cases where the monarchy directly benefited from such satirical abuses.

Royal targets or real people?

Since the 18th century, royal satire has broadly shifted from the Juvenalian mode (satire that is bitter, ironic, contemptuous, relentlessly extreme in its censure) to the Horatian (satire that is amused, tolerant and wry).

The latter is well exemplified by Harry Enfield’s The Windsors, which pokes gentle fun at royals, who are presented as dim-witted and detached, but ultimately harmless. It is to this Horatian tradition that The Prince is most openly indebted, with the show’s creator, Gary Janetti, even claiming that the show “is meant with affection”.

Though royal satire has become less scathing over time, it seems that audiences and critics have become more sensitive to jibes at this ruling elite, as the reception to The Prince demonstrates.

In some areas of the media, there is great concern that making fun of the monarchy might cause irreparable damage – that satire is in some way harmful to great tradition. More than anything, this perhaps speaks to the monarchy’s existential precarity when a light-hearted adult cartoon causes more concern to the crown than images of defecation, nudity and sexual promiscuity did 200 years ago.

The aspect of The Prince that has drawn the most fire is the decision to centre events around young Prince George, with the Daily Mail suggesting that children should be off-limits for satire.

Whether you agree, however, depends on whether you view George as the target of the show’s satire or its vehicle.

There is a rich tradition of child characters being used in satirical fiction to draw attention to the hypocrisies, inconsistencies and contradictions of the adult world. For example, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust (1934) features a child who is able to decode the true meaning behind the words of adults and immediately shares them in entertainingly blunt statements. A more recent example is Family Guy’s precocious Stewie Griffin – a character The Prince’s young George seems, in many ways, to recall.

The biggest problem faced by The Prince is that many members of the royal family no longer present themselves as aloof, but have instead come to be understood in language associated with popular cultural discussions, such as those surrounding racism and mental health.

Prince William and Prince Harry have both spoken openly about the loss of their mother, Diana and the effect this had on their mental health. Harry and Meghan’s interview with Oprah Winfrey in March 2021 touched on questions of race, gender and suicidal thoughts.

Both Princes have also been involved with charities raising awareness of mental health. When younger members of the royal family, at least, become humanised in this way, satire on the institution as a whole becomes more complex. It might seem that the more the family appears to be made up of “real people”, the more distasteful satire directed at them appears to some commentators.

Given this new climate, where those figures at the top of society are able to position themselves as vulnerable, “punching up” is no longer as easy to justify.