Why are there no chairs in the Bible, or in all 30,000 lines of Homer? Neither are there any in Shakespeare’s Hamlet – written in 1599. But by the middle of the 19th century, it is a completely different story. Charles Dickens’s Bleak House suddenly has 187 of them. What changed? With sitting being called “the new smoking”, we all know that spending too much time in chairs is bad for us. Not only are they unhealthy, but like air pollution, they are becoming almost impossible for modern humans to avoid.

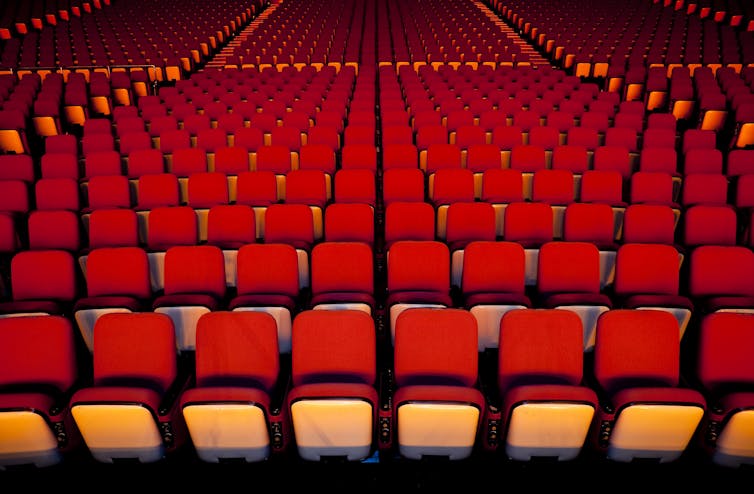

When I started researching my book about how the world we have made is changing our bodies, I was surprised to discover just how rare chairs used to be. Now they’re everywhere: offices, trains, cafés, restaurants, pubs, cars, trains, concert halls, cinemas, doctor’s surgeries, hospitals, theatres, schools, university lecture halls, and all over our houses (I guarantee you have more than you think).

If I was asked to make even a conservative estimate of the number of chairs in the world, I’d find it hard to go lower than 8-10 per person. Applying that logic, there could be more than 60 billion of them on the planet. Surely chairs should be one of the universal signals of the arrival of the Anthropocene? Just like the data required to justify the change in the name of our geological epoch, they are to be found on every continent.

As to why there are suddenly so many chairs, there is no single clear reason. It is a confluence of fashion, politics, changing work habits, and the lust for comfort. The last of these requires no explanation in a culture in which ease and comfort are among the strongest drivers of consumer decision-making.

A history of chairs

While chairs began to appear with a little more frequency in the early modern period, it seems that they became much more widely popular in the 18th and 19th centuries during the Industrial Revolution.

Before the 18th century, a chair was relatively easily come by, but the majority of the population had little use for them. Even today, it is not easy to sit in a hard wooden chair for sustained periods and upholstered chairs were prohibitively expensive. But the fashion for a new reclining culture (imported from the French court of the 18th century) helped to popularise their early use.

For centuries before, chairs had persistently been associated with power, wealth and high status. They were about as widely used by the peasantry as a crown. There is an instructive stage direction in the First Folio of King Lear in which the monarch enters while being carried by servants “in a chair”. The idea of chairs as a symbol of status still persists today. The highest attainment in my own profession, academia, is called “a chair”. The individual that runs a meeting is called “a chair”. The head of a company is also a chairman or woman. And it is a truth, universally acknowledged, that the best chair in any office building always belongs to the boss.

Once the use of chairs was democratised (particularly after the French Revolution in France and the 1832 Great Reform Acts in the UK), this coincided with a slow change in our working patterns. The majority of work done in the Victorian period would have been understood as manual labour or factory work.

But toward the end of the 19th century, as the second wave of a technological revolution gathered pace with inventions such as the typewriter, telegraphy and the expanding uses and applications of electricity, the labour market also began to change. The new category of office clerks were the fastest-growing occupational group in the latter half of the period. In 1851, the census suggests less than 44,000 people were performing administrative work. But in just two decades, sedentary workers had more than doubled to 91,000.

Read more: You should stand in meetings – don't worry about what others might think

A sedentary planet

Today, sedentary workers are in the majority. And, throughout the 20th century, a forest of other sedentary activities have grown up around us to match our new working lives.

Novel reading increased hugely in popularity throughout the 19th century – and further sedentary leisure activities followed in its wake: cinema, radio and TV. More recently, gaming, streaming and screen-time generally are all activities that are hungry for us to sit still in contemplation. The Anthropocene human needs chairs to fulfil all of these (I suppose we could call them) “activities”.

If modern life presents us with a bouquet of sedentary behaviours, then chairs are the stalks. They are so necessary to leading a modern life that most of what we do seems unimaginable without them. Research conducted by the British Heart Foundation suggests that we enjoy about 9.5 hours per day of sedentary time. This means that modern humans are inactive for about 75% of their time. There are a few problems with this.

Our bodies do their best to be the kinds of body that we need. Wolff’s Law and Davis’s Law can be boiled down to the adage “use it or lose it” for the body’s hard and soft tissues respectively. In both cases they tell us that muscle or bone will respond either to increased load or the cessation of use. Bones become thinner or denser. Muscles, stronger or weaker. Seated so much, with most of the musculature in our backs disengaged as they recline in a chair, it is little wonder that with our weakened spines, back pain is now the number one cause of disability, globally.

Just as we have an Anthropocene environment, we might equally class ourselves as Anthropocene humans. Palaeolithic humans died most frequently in infancy. Violence and injury were also common causes of mortality in later life. Modern humans, though, overwhelmingly die as a result of metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers – all strongly linked with inactivity: namely, chair use.

A 2012 study investigating the effects of inactivity collated behavioural data from 7,813 women and found that those that sat for ten hours a day had shorter telomeres (an indicator of cellular ageing). Their sedentary habits had aged them biologically by about eight years. Some studies even suggest that the effects of sitting for sustained periods cannot be offset by a little exercise.

These studies and many others attest to the fact that we should be thinking carefully about investing any further in our relatively new-found and passionate love affair with the chair.