With a reported 2m people running in the UK and an estimated 10m in the US, the activity is on the rise, and fast becoming the most popular form of exercise.

Running fits as snuggly into modern life as an eager foot into a plush pair of new trainers. It can be done alone and in almost any environment. As a solitary activity, there is no need to work around other people’s schedules. There are no courts, pitches, nets, bats, rackets or hoops necessary. You can just put on your shoes and go. It feels like the most natural way to exercise, but it has not always been this way. And it is not only these practicalities that motivate us.

Although running has a complicated history, we know that jogging as a “palliative to sedentariness” first took off in the 1960s. Since then it has become a huge business with the athletic shoe industry alone worth tens of billions of dollars.

Before the jogging revolution, though, it was a distinctly niche activity. The few people that did it had probably been to one of the more affluent schools. A quick leaf through the periodicals of the nineteenth century, such as Bell’s Life in London, and Sporting Chronicle, confirms it was a sport for gentlemen (and sometimes for the hustlers that conned them).

I have covered this more extensively in my research, but loosely defined, “sport” has been recorded since the beginning of documented history (The Epic of Gilgamesh from 3,500 years ago recounts scenes of wrestling and hunting) and it has been a regular mainstay of literature since then. But, exercise, as we might recognise it, being movement for the purposes of maintaining physical health, only becomes common as recently as the early nineteenth century.

We can see it in Jane Austen novels. Fanny in Mansfield Park is forever “knocked up” on the sofa as the result of a good walk, but exercise is mostly a pastime for the daughters of gentry, for whom the competition inherent in sport would not be appropriately gendered behaviour. Austen also uses the idea of exercise and movement to pass judgement on her characters: generally, those who over-indulge in it are villainous or not to be trusted, and those who possess more moderate appetites for it are usually our hero or heroine. The finest walker in Austen is Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennet, who seemingly strikes just the right balance when she arrives at Netherfield with flushed cheeks and muddy skirts to visit her sister – surely, the Georgian equivalent of a trail run.

By the nineteenth century, then, exercise emerges as an activity commonly seen around the leisured classes. Without physical work, their bodies wither and weaken, so must be exercised. Which is where the inventors came in.

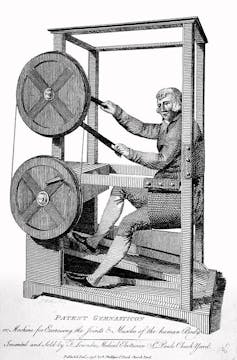

In 1797, the Monthly Magazine announced a new patent for Francis Lowndes’s Gymnasticon, the earliest of static exercise machines. The magazine explained that it may be of use “when peculiar or sedentary occupations enforce confinement to the house”.

Whenever I have displayed this image at a talk, it is guaranteed to make the audience laugh. It seems such an undignified contraption. But how different is it to, say, a cross-trainer?

Austen’s suspicion of exercise seems to hold true for us today. People will run in parks, but won’t do aerobics workouts in them. P.G. Wodehouse was right in his first Blandings novel, Something Fresh (1915), in which he explained that anyone who wished to exercise outdoors in London had a choice: either give up, “or else defy London’s unwritten law and brave London’s mockery”. But if exercise is degrading why, as every year goes by, are there more runners?

Not to be mocked

The answer is that you only have to put on a TV to see that sport is respected worldwide, but exercise is not revered in the same way. And I think that running is popular because it has its feet in both camps of sport and exercise. It is a permissible public activity because of its associations with sport (unlike Zumba or Body Pump, for example).

The industrial revolution has swept away most of our forests and green spaces, and in doing so changed completely our ways of working, leaving us desperately searching for the easiest means to exercise because it is no longer a part of our working day, but an addition to it.

The number of runners will only continue to increase in the coming years, as austerity bites and convinces us to work ever longer hours, over more days. In rejecting our lethargy, we will continue to look to the easiest, cheapest and most accessible and enjoyable activity that we can. Running remains just about the only intense aerobic activity that does not require you to brave London’s mockery.

And, it’s terrific fun.